FLOATING WEEDS

A film by Yasujirô Ozu

1959/ Japan/ 119 minutes

5.45 pm / 4th Sept/ 2016 / Perks Mini Theater

Sooner or

later, everyone who loves movies comes to Ozu. He is the quietest and gentlest

of directors, the most humanistic, the most serene. But the emotions that flow

through his films are strong and deep, because they reflect the things we care

about the most.“Floating Weeds” (1959) is like a familiar piece of music that

you can turn to for reassurance and consolation. It is so atmospheric--so

evocative of a quiet fishing village during a hot and muggy summer--that it

envelops you. Its characters are like neighbors.

A panoramic,

low angle opening montage of an idyllic Japanese coastal province defines the

understated, cinematic poetry of Yasujiro Ozu: a lighthouse framed against a

tranquil sea; docked boats undulating with the sweeping waves; villagers

weaving lackadaisically through local shops, as much for social interaction as

for commerce.

A struggling, itinerant acting troupe arrives into town for a

kabuki show, lead by an aging performer, Master Komajuro . It is a tenuous

homecoming for Komajuro. Ozu expertly weaves the narrarative through Komajuro's

life, his women, his son and unexpected

setbacks that he faces.

Ozu's pervasive

use of low camera height provides more than just a directorial signature style

in Floating Weeds. As in Tokyo Story, the atmosphere is intimate and

accessible. The characters appear grounded, human, reflecting Ozu's respect for

the dignity of the common man. The camera does not wander, but retains focus on

the space, creating a unbiased perspective of the characters.

Inevitably, we

understand Komajuro because he is all too human: the aging actor at the

twilight of his career; the leader faced with the dissolution of his failed

troupe; the father ashamed to reveal his deception. He has transcended the

great samurais of his struggling plays, stripped of their cosmetic facade, and

is rewarded with compassion and humanity. "Nothing is constant under the

sun," someone observes, and this is very much a film which acknowledges

the transience of human lives.

Ozu was born

on December 12, 1903 in Tokyo. He and his two brothers were educated in the

countryside, in Matsuzaka, whilst his father sold fertilizer in Tokyo. Ozu

developed a love of film during his early days of school truancy, but his

fascination began when he first saw a Matsunosuke historical spectacular at the

Atagoza cinema in Matsuzaka. Ozu's uncle, aware of his nephew's love of film,

introduced him to Teihiro Tsutsumi, then manager of Shochiku. Not long after,

Ozu began working for the great studio—against his father's wishes—as an

assistant cameraman.

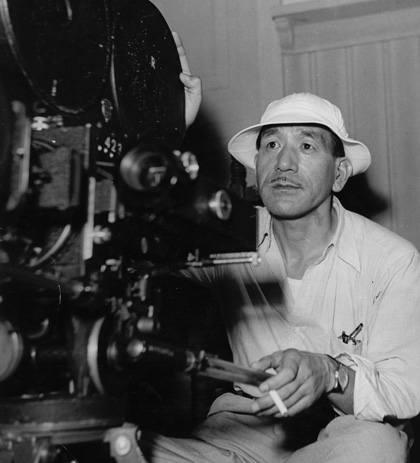

Yasujirô Ozu

Ozu's work as

assistant cameraman involved pure physical labour, lifting and moving equipment

at Shochiku's TokyoThe Sword Of Penitence that became his first film as

director (and only period piece) in 1927. Ozu was called up into the army

reserves before shooting was completed. No negative, prints or script exist of

The Sword Of Penitence—and, sadly, only 36 out of 54 Ozu films still exist.

studios in Kamata. After becoming assistant director to Tadamoto Okubo, it took

less than a year for Ozu to put his first script forward for filming. It was in

fact his second script.

Days Of Youth

(Wakaki Hi, 1929) is Ozu's earliest extant picture, though not especially

typical (and preceded by seven others, now lost) as it is set on ski slopes.

Stylistically it is rife with close-ups, fade-outs and tracking shots, all of

which Ozu was later to leave behind. Three years later came what is generally

recognized as Ozu's first major film, I Was Born, But... (Umarete wa Mita

Keredo..., 1932). This moving comedy/drama was a great success in Japan both

critically and financially. It was one of cinema's finest works about children.

Thirty years into his filmmaking career Ozu was making films which, like

Kurosawa's Ikiru (1952), questioned the sense of spending your whole working

life behind a desk—something that many of his audience must have been doing.

Ozu's films represent a lifelong study of the Japanese family and the changes

that a family unit experiences. He ennobles the humdrum world of the

middle-class family and has been regarded as “the most Japanese of all

filmmakers”, not just by Western critics, but also by his countrymen.

No comments:

Post a Comment